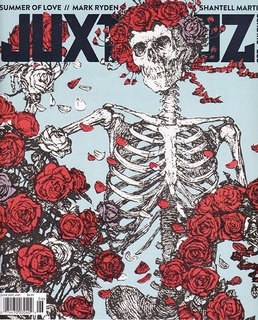

Juxtapoz: Shiri Mordechay Interview by Gabe Scott

Shiri Mordechay: An Insomniac's Garden

May 26, 2017

The large-scale paintings of New York Painter Shiri Mordechay are an enveloping feast for the senses, like physically entering a pop-up book pulsating in fevered optics. Somewhere between reality and a garden of other earthly delights lies the psyche of this visionary, a vessel of mysticism, supernatural environs, memory and clairvoyance. A certain level of bravery is required for weaving these teeming tapestries of the entranced, and the results can be staggering. Delving into the depths of myth, trauma and other personal experience, she creates her own shamanic process to commune with her unconscious, acting as conductor for a surreal visual symphony.

Gabe Scott: I think maybe the best place to start is in 2012 at Honor Fraser in Los Angeles, with your sprawling exhibition, Pneuma Pleats. It really seems that, after three years working on the piece, this opened the floodgates, in terms of releasing the mythology. I’d like to better understand some key points of its creation, including your process.

Shiri Mordechay: In that piece, specifically, I wanted to engage the most primal part of myself without censorship-and spent nearly three years making it. The title, Pneuma Pleats, comes from the work breath: when you breathe, you create the world. I think I have a wish to let the floodgates of my subconscious be open, but in this piece, it was more concentrated, or more focused. Honor Fraser gave me free range and told me to do what I wanted. There is a long tradition of artists working on a piece for long periods of time, such as Michelangelo, or the pyramids, and so on. It’s like writing a novel that can take a long time to travel through. The anatomical fragmentation in this piece acts like visual chapters or a vignette, which I weave out together to see how they translate, or come together like a fabric. God creates parts of things, and so can I. I think of the artist as a reporter.

With respect to the tormented sexuality, within the unconscious, we have all that potential, and I experiment with different scenarios without any moralizing. Painting gives you permission to be free this way, so I have used sexuality in a way to talk about violence and survival. Another aspect is my interests in how these images affect the viewer, how it makes them feel. Those types of questions are interesting to me.

Gabe Scott: How does your approach to Pneuma Pleats compare to previous shows, particularly the Serpents of the Rainbow installation at Alter Space in San Francisco?

Shiri Mordechay: I used to work with pastels more, but that was a long time ago. I think this changed because of living in small spaces. I was living in New York without studio space for long periods of time. So I really had to work just wherever I was. I usually don’t get to see the finished product in its entirety until it is hung.

Gabe Scott: How Does working in a confined space affect your process? Have you simply learned to adapt? I would imagine it being a considerable challenge to visualize such complex three-dimensional works hampered by spatial limitation, particularly with so many components.

Shiri Mordechay: It’s like being metaphorically blindfolded in a way, which means I rely on just trusting it so everything can be reassembled. It’s very flexible, an improvisation.

Gabe Scott: When you’re actually able to lay it all out in an exhibition setting, how much does it resemble what you’ve envisioned?

Shiri Mordechay: It really morphs when you create in such a small area and then transfer your stuff to a huge space. What happens is, all of a sudden, I freak out because I realize how much is needed. For me, it takes over the entire world in my tiny basement. It’s living all over. Sometimes when I see the work in a new space, I see that it is no longer the same piece. It takes on a new life and grows to confirm to the new environment. I feel I have to continue and add new parts. So, in conclusion, I think it’s like taking a tiny fish that was raised in an aquarium that is thrown into the sea. It behaves differently…

Gabe Scott: What do you mean when you say you’re not satisfied? Does it feel incomplete?

Shiri Mordechay: It’s really like a never-ending story. One thing leads to the next and goes on forever. I could never stop growing it, even if I wanted. The work is pretty much driven by process and I can continue to animate the piece. Just sitting here looking at my work, my eye keeps following the story and I imagine where it may move all over the room. Of course, when you look at my work, one can see how much detail there is in each section. It takes a long, long time to create a single image. But it’s infinite, the way I continue to see it. In a way, I commune with it like an actual organism.

Gabe Scott: At what point in your process do you decide to stop and feel comfortable presenting the piece?

Shiri Mordechay: That’s a good question. I change my mind so many times; having a deadline helps. But I’m confortable enough when it’s independent of me. It talks back and announces itself, “I can see you.”

Gabe Scott: Now that’s one way of having a dialogue with your work. I would imagine that usually it would be more of a one-way street between creator and creation.

Shiri Mordechay: Yeah, but then, of course, I change my mind right away. And if I move it to another corner, it would say something else. The work is nature in itself. I don’t mean for it to be this way. But it’s like having a silent, telepathic dialogue.

Gabe Scott: What serves as the base of your source material in these paintings?

Shiri Mordechay: I pretty much live my life not sleeping. As much as I look at something, I change of lot of the imagery, so it’s vivid and I do a lot of mental projection. The images I see are very active and demanding, a lot that’s related to the rest of my body. When I look at something, my imagination expands and also blends with my emotions.

Gabe Scott: Have you had insomnia and an overactive imagination since you were young?

Shiri Mordechay: Always, every since the time I remember.

Gabe Scott: Can you draw or explain any parallels between your sleep deprivation and your lively imagination?

Shiri Mordechay: The insomnia sort of creates interesting states of mind, changing your consciousness because a part of you is exhausted and the other part is hyperstimulated. So I get a lot of different images that come to me. It’s a weird thing, because I would love to get the sleep, but at the same time, it avails other visions, so it’s like pleasant masochism.

Gabe Scott: Obviously, part of many different stories here are linked by some common threads, bud as you said, not necessarily in linear narrative. Many elements of your conscious mind are apparent, and perhaps others that aren’t, are woven into the fabric. Do you have a central point from which you work outwardly or can you begin with a number of the smaller, individual components?

Shiri Mordechay: Every single scrap I make fits somewhere perfectly, if not now, then maybe a year form now. But usually things have a way of just falling into place. I can start from anywhere, you know? This is the process, different seeds falling and each, the beginning of a life.

Gabe Scott: What are some of the key binding elements tying everything together in The Serpents of the Rainbow? Each of your undertakings feel like an individual world, not as an exhibition of paintings with their own individual cognition, operating under the same thematic umbrella.

Shiri Mordechay: There is a focal point here, what is happening between these two figures. I don’t know if the figure on the right is a kid of priest, but the performs some kind of ritualistic purpose, not necessarily in a religious context, although there may be some layers of that. This entire piece exists between worlds, and the meaning rests on the borderline of ecstatic experience. The work is never just one thing. It does not get rounded into only one psychic action or thing. It lives in worlds of water and evaporated steam. I guest you would see some of the things here as landscape and characters, things that arise to build a story or dynamic like the fish and water. I don’t like to make it about a singular narrative, but as a fractured one. It is like when you take a car ride…the scenery changes really fast, moving onto another street. There is a series of movie frames or scenarios that form something solid, and as the movie frame comes into focus, all at once it makes sense. I feel like the process resembles how one reads a thought, a series of powerful scenes flicking by the mind’s spiritual lens.

Gabe Scott: How do you envision your process, as painting, sculptural undertaking or installation?

Shiri Mordechay: My work is a painting. The word installation does not represent my work. I see it as a three-dimensional hung painting, and this is what I think when I make it. It is born from a painting.

Gabe Scott: I know that a lot of the tribalism in Nigeria, where you grew up, features a shaman for each group, tribe or village. Was that a basis for your interest in the role and potential of the shamanistic state ofmind? Has that influenced the direcitonn of your personal exploration?

Shiri Mordechay: I think how you are wired is instinctual and comes from a more primitive part of your brain. I lived in Benin and Calabar, where my father was working in construction. I stayed there till age ten, and then we moved to Israel for two and a half years, where my family is from. Then I moved to LA when I was twelve or so. The first house we lived in was right by the jungle, isolated from communities, and the tribes would knock in our house with juju rituals which scared me; I would see supernatural events, and the tribal person with the masks would dance naked and tell me to go with him. He would shapeshift in front of my eyes, hypnotize me. I have nightmares to this day.

Shiri Mordechay: Because the labor takes so long, there are days and months, sometimes years of your life where so much information is processed and not everything is going to last. Sometimes something will break down in the middle and then you go somewhere else. There is a repetitive theme, and in this specific show at Alter Space, a lot of Asian scenes. They have human qualities not from our universe, a lot, again, from me not sleeping at night.

As an example, here’s a short story: I painted this a while ago, but months and month afterwards, there was one morning that I was really tired from not sleeping the previous night. I felt myself go into a kind of a trance, like out of my body, and all of a sudden, this beautiful Asian creature crossed my path. She was half a bird with amazing gorgeous eyes, and our eyes accidentally met. It was a very visceral experience, like a meeting with nature. Then, in a split second, she transferred all of the worlds I’d been painting for months and months but hadn’t put together. She looked at me and I looked at her, and it had nothing to do with the painting. Afterwards, during the day, I realized it was like meeting a leopard in the forest or jungle accidentally. So she transported to me everything about the universe I’d been painting. So I think its like all these channels and different buttons. She came from an underworld of water where these creatures have a different rule system and have a bird hybrid within. So again, the way I work is not linear.

Gabe Scott: Most recent you were involved in a group show with Diane Rosenstein, inspired by the Talking Heads classic “Life During Wartime.” The exhibit, which borrowed the title, centered on many of contemporary society’s most divisive issues: the skewed diagram in America for economics and classism, as well as inequality of race and gender. Given that so much of your work is about the surreal and the subconscious, how did you approach this more sociological assignment?

Shiri Mordechay: At the Diane Rosenstein exhibition, I had two rooms of paintings. I made this piece at a studio in downtown LA, where themes were the semantic influence that arose when creating violence and hopelessness and what happens to the human spirit in desolation row. The me, “Life During Wartime” is a sort of war on existence, such as God and the Angels, spirit and body, the war in our sols. My work is a different type of surrealism, not akin to the original Surrealist movement. From the beginning, they were more politically motivated, but they did believe that liberation of the unconscious liberated bourgeoisie repressions, and I can relate to this aspect. But my work is not classical surrealism. My images are partly dream state mixed with real life, I depict detailed objects using distinct codes and making combinations of images that emanate from a real place.

Gabe Scott: Whatever you present in each piece, it ‘s as if you invite many different ideas and allow them to move about freely, around a naked structure, when at a certain point, an idea or impulse will cause them to fuse into place and be visualized while the energy continues to circulate until order is determined. The ideas seem to multiply and cross-pollinate with one another, whether form an actual, physical place or from your mind’s eye.

Shiri Mordechay: Yes, that makes sense, and it makes itself. I am drawn to certain things, but I feel like I’m just the maker or the conduit. I’m just a body that allows things in.